Recent mob outbreaks in Times Square have people concerned about rising levels of violence in the city. For some it evokes the city's reputation from the 1970s. But New York City has always held a bit of a reputation:

In small clusters, the world began coming to North America via this island nestled in its inviting harbor. And while the West India Company had a firm Calvinist stamp to it, which it tried to impress on its colony, the makeup of the settlement—itself a result of the mix of peoples welcomed to its parent city of Amsterdam—helped to ensure a raggedness, a social looseness ... Days got livelier; with nightfall, the soft slap of waves along the shore was drowned out by drinking songs and angry curses (Shorto 2005: 61).

My suspicion is that the concerns about New York City today echo sentiments about New York City in the 1970s, which echo the sentiments expressed about New York City in the 1830s—when New York City was home to one of the most notorious slums in the world, the Five Points.

In other words, the time of present memory is almost always the most dire circumstance. I invite you to journey back in time with me to walk the streets of the Five Points, and draw your own conclusions about the intersection of the city's past and present. But before you secure your valuables and venture into the alleys and tenements of the area, let's look a bit at the history.

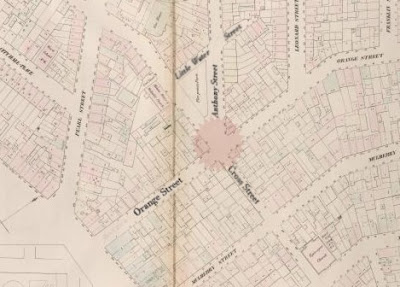

Also known as New York City's Sixth Ward (in terms of voting districts), the Five Points was marked by the boundaries of present day Canal, Centre, and Chatham Streets, and the Bowery (which today loosely marks the boundaries of Chinatown). It was so named by a newspaper in 1829 in reference to the intersection of the five corners at Anthony, Orange, and Cross Streets—all of which were later renamed in an effort to stamp out all traces of the neighborhood, which was viewed as a veritable den of iniquity. Today, a playground sits at the intersection of this once notorious address, where bandits and prostitutes once roamed freely. [Map from the 1850s showing the intersection of Anthony [Worth], Orange [Baxter], and Cross [Park] Streets. Due to changes in the grid, today all that remains of the namesake of the Five Points is the intersection of Worth and Baxter Streets.]

Also known as New York City's Sixth Ward (in terms of voting districts), the Five Points was marked by the boundaries of present day Canal, Centre, and Chatham Streets, and the Bowery (which today loosely marks the boundaries of Chinatown). It was so named by a newspaper in 1829 in reference to the intersection of the five corners at Anthony, Orange, and Cross Streets—all of which were later renamed in an effort to stamp out all traces of the neighborhood, which was viewed as a veritable den of iniquity. Today, a playground sits at the intersection of this once notorious address, where bandits and prostitutes once roamed freely. [Map from the 1850s showing the intersection of Anthony [Worth], Orange [Baxter], and Cross [Park] Streets. Due to changes in the grid, today all that remains of the namesake of the Five Points is the intersection of Worth and Baxter Streets.]The history of the Five Points is tied closely to industrialization and immigration. The neighborhood was situated at the site of the Collect Pond—once a beautiful body of water, it was quickly soured by the tanneries that set up along its banks. The city filled in the pond, changing the landscape, with the intention of providing additional housing for the growing burg. However, the marshy land never really settled properly and as a result, the buildings constructed on the site would tilt and tended to sink. The remaining businesses in the area fled as a result. Floods were common in the area and because diseases were often linked to dampness, very few New Yorkers wanted to live in the area.

That left the space available to African Americans and immigrants, two groups that faced prejudice in terms of the occupations available to them and as a result had little savings, so the low rents of the Five Points were particularly appealing. The neighborhood would become home to the large Irish population that fled the the potato famine seeking opportunities for advancement in America. And as the Irish Catholics moved in, the native-born Protestants living in the area moved away—a pattern that is repeated in neighborhood shifts with one group replacing another.

According to Five Points historian Tyler Anbinder, what sealed the reputation of the neighborhood was the proliferation of prostitutes and brothels. The trade shifted from nearby Water Street in the 1830s to Anthony Street (between Centre and Orange). Anbinder speculates that location was likely the draw for prostitutes looking to ply their trade—the Five Points was strategically positioned within walking distance (25 minutes) from most populated areas on the island. The large population of unfettered immigrant men also increased the customer base for this business.

The Five Points, as depicted by George Catlin, 1827. From Anbinder: Note the prostitute hanging out of the window in the upper right. She is more visible in the black and white print below.

As the area filled beyond capacity, newspaper accounts paint a dismal picture, with drunkenness, thievery, rioting, and disease as characteristics of the neighborhood. And while Anbinder cautions against the sensationalized view presented in newspapers of the time, he himself writes:

Even if one considers only the statements of Five Pointers themselves, rather than the biased views of outsiders, one finds a neighborhood rife with vice, crime, and misery. Brothels were everywhere. Alcoholism was omnipresent. Habitually drunkard men beat their wives and children. The neighborhood's many female alcoholics neglected their sons and daughters, producing some of the Five Points' most heart-rending tales of abuse and suffering. Upwards of 1,000 Five Pointers at any given time lived in filthy, overcrowded, disease-ridden, tumbledown tenements whose conditions are unimaginable to modern Americans (2001: 4).

The Five Points managed to both attract and repel sensibilities. Notable figures, including Davey Crockett and Charles Dickens toured the neighborhood, and helped spread word of its reputation first throughout the nation and then throughout the world. Dickens compared the area to St. Giles, a notorious English slum:

Here, too, are lanes and alleys paved with mud knee deep, underground chambers, where they dance and game ... hideous tenements which take their name from robbery and murder; all that is loathsome, drooping, and decayed is here (Anbinder 2001: 33)

The practice of "slumming," in the company of a police escort, soon became a means of entertainment for the wealthier classes interested in seeing what life was like on the other side of the poverty line. By the way, it seems the practice has been dressed up a bit but still alive: San Francisco is encouraging visitors to visit the Tenderloin district, known for its grittiness, to experience, well, a different side of life:

The Tenderloin is one of the mostly densely populated areas west of the Mississippi, officials say, with some 30,000 people in 60 square blocks, almost all of which have at least one residential hotel. The district’s drug trade is so widespread, and so wide open, that the police recently asked for special powers to disperse crowds on certain streets. Deranged residents are a constant presence, and after dark the neighborhood can seem downright sinister, with drunken people collapsed on streets and others furtively smoking pipes in doorways.

Sound familiar? It's a helpful notation to bear in mind when considering that even as New Yorkers called for reforming the Five Points, it played a vital role in helping to "otherize" particular groups of people.

"Doing the Slums," Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1885.

As terrifying a portrait of the Five Points as is depicted, the area was a major force in the political landscape—its residents were, after all, the first working class New Yorkers. And major cultural markers also emerged from the area, including tap dancing (a mix of the Irish jig and African shuffle). Widely publicized and immensely popular bare knuckle prize fights also had a home here. What often gets lost in the cloud of misery that hangs over the Five Points is the story of how these residents shaped their lives. The Irish who settled here worked hard to establish themselves amidst their drunken neighbors, and eventually moved out, to be replaced by the Chinese who were also initially viewed in a very similar light.

Today, remnants of the Five Points haunts Chinatown, which contains some of the flavor of the original neighborhood. In the coming posts, we'll explore some infamous sites looking at the past and present of the neighborhood and delve into the tenements.

Stay tuned.

Sources:

Anbinder, Tyler. (2001) Five Points. New York: Penguin Group.

Shorto, Russell. (2005) Island at the Center of the World. New York: Doubleday.

Sources:

Anbinder, Tyler. (2001) Five Points. New York: Penguin Group.

Shorto, Russell. (2005) Island at the Center of the World. New York: Doubleday.

unrelated to the 5 points but thought you might like to know about this art project on ettiquette in the NY subways

ReplyDeletehttp://animalnewyork.com/2010/04/artist-promotes-subway-etiquette-with-guerrilla-campaign/

Thanks for the link - actually fits nicely with some disturbing LIRR behavior I was planning to write about.

ReplyDelete